1.119.716

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

Machu Picchu

| Kiadó: | Newsweek, Inc. |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | New York |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Vászon |

| Oldalszám: | 172 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 29 cm x 23 cm |

| ISBN: | 0-88225-302-6 |

| Megjegyzés: | Fekete-fehér és színes fotókkal, illusztrációkkal. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

TovábbFülszöveg

Lost city of the incas—the words are as much an incantation as an identifying label, and over the past five centuries they have enticed uncounted adventurers into the virtually impenetrable jungle that lies northwest of Cuzco, the former capital of the Inca's Peruvian empire. What those adventurers were searching for was a place called Vilcabamba, the last refuge of the royal Inca and the remnants of his court. Many also hoped to uncover the legendary, long-missing golden treasure of the Incas, said to be buried at Vilcabamba. What those who braved the jungle found was—more jungle. And, along the route, white water that could not be forded, sheer cliffs that could not be scaled, pesky mosquitos and poisonous snakes.

Vilcabamba, it seemed, had been enveloped by the mountain mists, the voracious vegetation of the rainforest, and the myths that breed there. But unlike El Dorado, exclusively a figment of the Western imagination, Vilcabamba had existed at one time. The followers of... Tovább

Fülszöveg

Lost city of the incas—the words are as much an incantation as an identifying label, and over the past five centuries they have enticed uncounted adventurers into the virtually impenetrable jungle that lies northwest of Cuzco, the former capital of the Inca's Peruvian empire. What those adventurers were searching for was a place called Vilcabamba, the last refuge of the royal Inca and the remnants of his court. Many also hoped to uncover the legendary, long-missing golden treasure of the Incas, said to be buried at Vilcabamba. What those who braved the jungle found was—more jungle. And, along the route, white water that could not be forded, sheer cliffs that could not be scaled, pesky mosquitos and poisonous snakes.

Vilcabamba, it seemed, had been enveloped by the mountain mists, the voracious vegetation of the rainforest, and the myths that breed there. But unlike El Dorado, exclusively a figment of the Western imagination, Vilcabamba had existed at one time. The followers of Francisco Pizarro, who conquered the Inca empire in 1534, were to visit Vilcabamba on a number of occasions—the last a punitive military expedition that reached the torched settlement in 1572—and the chroniclers of the Conquest left detailed accounts of this last citadel of the Incas.

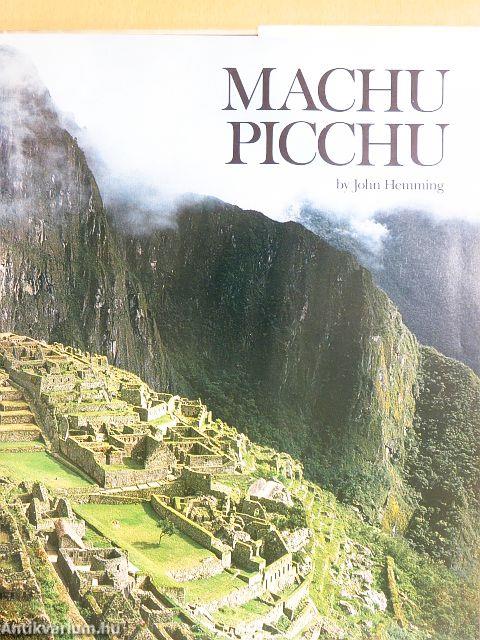

And so the search for Vilcabamba continued over the centuries—all to httle avail until 1911, when a young explorer named Hiram Bingham made what certainly ranks as one of the most remarkable anthropological discoveries of this century. On a sharp granite ridge some 2,000 feet above the roaring Urubamba River stood an Inca city that the conquistadores had never discovered. It lay beneath a mantle of jungle creepers, which had to be cleared away, but its state of preservation was extraordinary. Bingham was convinced that this place, which the indigenous peasants, descendants of the once-mighty Incas, called Machu Picchu, was in fact Vilcabamba—and for half a century his theory encountered few detractors.

We now know that Machu Picchu is not Vilcabamba—whose location, even deeper within the Amazonian rainforest, was confirmed in the 1960s—but that does not detract in any significant way from the magnificence of Bingham's Lost City of the Incas. It remains the finest aggregation of Inca buildings in all of Peru—and one of the most breathtaking

(conlinued on back Jlap)

.«».a

f continued from front flap)

anthropological sites in all the world. Its gabled houses, numerous temples, and terraced fields are a compendium of Inca stoneworking techniques—and their survival is a tribute to the skills of the New World's preeminent masons.

So perfectly preserved is Bingham's city in the clouds that we have little trouble imagining life in this Inca aerie in its heyday—the busy hum of activity in the Convent of the Sacred Women, who attended the Inca; the solemn ceremonies at the Hitching-post of the Sun, the center of Machu Picchu's religious rites; the eerie silence of the Royal Mausoleum, where the mummified remains of Inca monarchs were preserved.

There is much that we do not know, and never will know, about Machu Picchu—why it was built, how often and how long it was occupied, why it was abandoned without apparent struggle. But our ignorance of these historical details in no way diminishes the significance of Hiram Bingham's discovery. Machu Picchu is the Lost City of the Incas, in fact as in popular estimation, and the mysteries that now surround its construction, its use, and its eventual abandonment only serve to enhance its hold on our imagination. It is, in a sense, appropriately enigmatic: remote, romantic, mythopoeic, and magical.

John Hemming, author of Machu Picchu, is the director of the Royal Geographical Society in London and the author of Conquest of the Incas, a definitive history of sixteenth-century Peru based upon the chronicles of the Conquest.

Machu Picchu is a new volume in the Newsweek Book Division's series of illustrated histories. Wonders of Man. Each volume, focusing upon a well-known historical monument, is divided into three major sections: a lively history of the monument by a distinguished writer, profusely illustrated in color and black and white; a selection of literary excerpts about the monument; and a reference section including a guide to the monument, a chronology, a selected bibliography and full picture credits, and a complete index. Other titles in the series include: Mecca, The Forbidden City, Venice, Kyoto, The Taj Mahal, and Tower of London.

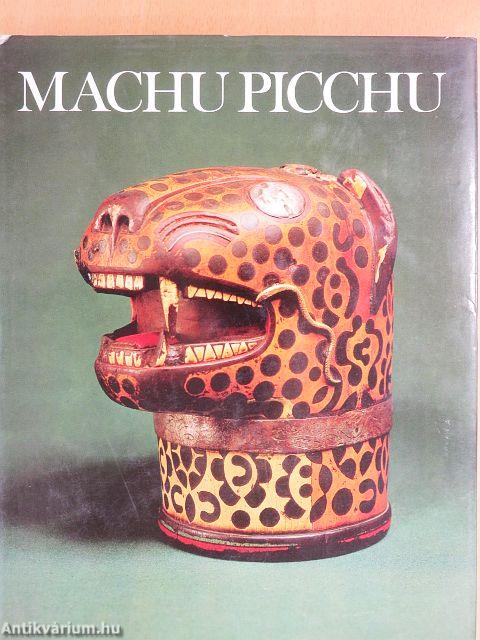

jacket illustration: This Inca kero, or wooden drinking cup—shaped lo resemble the head of the puma, one of the Incas' feline deides—has been finished in brilliant polychrome and embellished wilh a silver neckband and silver whiskers. A small gold snake peers into the puma's gaping jaws. Vissza

Témakörök

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művészetek > Művészettörténet, általános

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Művelődéstörténet

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Történelem > Egyéb

- Művelődéstörténet > Civilizációtörténet > Amerikai

- Művelődéstörténet > Kultúra > Kultúrantropológia

- Művészetek > Művészettörténet általános > Kontinensek művészete > Amerika

- Művészetek > Művészettörténet általános > Idegen nyelv > Angol

- Művészetek > Művészettörténet általános > Művészettörténet > Külföldi

- Történelem > Idegennyelvű > Angol

- Régészet > Kontinensek szerint > Amerika

- Történelem > Kontinensek szerint > Amerika, amerikai országok története > Egyéb

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Régészet > Kontinensek szerint > Amerika

- Történelem > Régészet > Kontinensek szerint > Amerika

John Hemming

John Hemming műveinek az Antikvarium.hu-n kapható vagy előjegyezhető listáját itt tekintheti meg: John Hemming könyvek, művekMegvásárolható példányok

Nincs megvásárolható példány

A könyv összes megrendelhető példánya elfogyott. Ha kívánja, előjegyezheti a könyvet, és amint a könyv egy újabb példánya elérhető lesz, értesítjük.